The whole idea behind this write up is to make each and everyone understand the complex box office model in India. Any questions, please ask in the comments section below.

Producer: The person who invests in films. The money that a Producer invests in making a film is called the “Budget”. It includes everything from remuneration of the actors, technicians and other crew members to transportation and other costs. Apart from this, once a film is complete, it has to be marketed and that calls for “PA (Promotion & Advertisement)” expenses.

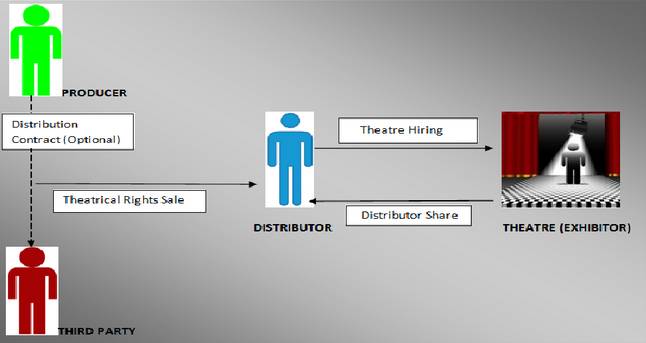

Distributor: The Distributor forms the most vital link in this money chain by acting as a medium between Producers and Theatres. The Producer has to deal out their film to the All India Distributors. The price at which the producer sells his film to the distributors is termed as “Theatrical Rights”. The producer can either directly sell the Theatrical Rights to Distributors or make a contract with any Third Party which in turn has the responsibility to deal with Distributors. In that case the Producer will get his share from the third-party even before his film releases and all Profit/Loss will be incurred by third-party only. For example, Yash Raj Films distribute their films themselves, while Nadiadwala Grandson’s had a contract with EROS for Housefull 2. Indian film industry is majorly distributed in 14 circuits and each have its distributors to represent them :- Mumbai, Delhi/UP, East Punjab, CI (Central India), CP Berar (Central Provinces), Rajasthan, Bihar, West Bengal, Nizam, Mysore, Tamil Nadu, Assam, Orissa and Kerala.

Exhibitor (Theatre): In layman terms, Exhibitor is nothing but a theatre owner. The theatres form the end of the box office model. On pre-defined agreements with the exhibitors, the distributors hire their theatres to showcase films. There are two types of theatres in India: (i) Single Screens (ii) Multiplex Chains and both have different kind of agreements with distributors. This agreement focuses mainly on “Number of Screens” and “Monetary Returns” to be paid back by theatres to Distributors. Entertainment Tax (All India average of 30% approx) is deducted from the total collections at the ticket window. This tax is enforced by individual state governments and thus differs from circuit to circuit. After taxes, a percentage of the total nett gross is paid back to the Distributors. This return is known as “Distributor Share”.

Box Office Terminology:

- 1) Cost of Film = [Budget + PA (Promotion & Advertisement) Expenses]

- 2) Non Theatrical Revenues = Satellite Rights + Music Rights + Overseas subsidy etc.

- 3) Footfalls = Total number of tickets Sold

- 4) Gross Collections = Total money collected from ticket sales

- 5) Net Collections = [Gross collections – Entertainment Tax and others]

- 6) Distributor Share is generally calculated as below:

| Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Thereafter | |

| Multiplex | 50% | 42% | 37% | 30% |

| Single Screens | 70-90% | 70-90% | 70-90% | 70-90% |

This means 50% of the collections (after entertainment taxes) goes to the Distributor in the first week of release and so on.

- 7) Profit / Loss (Distributor) = [ Amount at which film was bought – Distributor Share ]

Let us now go through a scenario to better understand about these terms.

Case Study – Suppose a film releases with an average ticket price of Rs 120 at Multiplex and Rs 60 at Single Screens in Week 1. 100 people visit a multiplex and single screen each. Entertainment Tax to be deducted from gross collections is same as 30%.

| Multiplex | Single Screen | |

| Footfall | 100 | 100 |

| Average Ticket Price | 120 | 60 |

| Gross Collection | 100 * 120 = 12000 | 100 * 60 = 6000 |

| Entertainment Tax | 0.3 * 12000 = 3600 | 0.3 * 6000 = 1800 |

| Net Collection | 12000 – 3600 = 8400 | 6000 – 1800 = 4200 |

| Distributor Share | Fixed 4200(50% — > 0.5 * 8400 = 4200) | Between 2940 and 3780(70% — > 0.7 * 4200 = 2940 /90% — > 0.9 * 4200 = 3780) |

Highlights

Multiplex v/s Single Screen: It is quite an inevitable fact that Multiplexes have been dominating the box office with every passing year; still the strength of Single Screens can’t be ignored. Single Screens may be termed as the backbone of Distributor Share for the consistent contribution they make and even today, when it comes to making/breaking big records, a film cannot bypass Single Screens.

Hit vs Flop: General norm is that the collection of a film judges how big success it is. But, this is false. In reality it is the Distributor Share which decides a film’s fate because it takes into account both the film’s cost & its box office performance. A film may be called a FLOP fare if it collects 60cr net because of its huge costs to the makers and distributors. On the contrary, another film may turn out to be HIT even if nets 40cr only due to low budget.

Footfalls – An Untold Story: While writing this article, I realized that there is a parameter which is not quite explored/considered in judging box office numbers. And that is Footfalls – i.e the number of people going to watch a film in theatre. One may figure out quickly from above facts that even if more people visit a Single Screen than a Multiplex, Multiplex always has a lead due to high ticket prices.